The most frequent question I get asked, by Israelis and non-Israelis alike, is why I moved to Israel.

The non-Israelis – English primarily – can’t understand why I would have wanted to leave the country of my birth (and first 28 years). Whenever there is any kind of sporting contest between their (our?) country and my adopted one, the English cannot fathom why I support Israel. And, when we get inebriated on the Friday evening of my annual visit to Harrogate, my mate John, a good, solid Yorkshireman, always sets me his own version of the Tebbit Test: “If there was a war between England and Israel, who would you fight for?” Suffice it to say, my answer – like John’s question, the same every year – always leaves him shaking his head, lips clenched.

Many – perhaps even most – Israelis I meet, too, can’t understand why I chose what they consider a far harder life. Following a brief discourse on Israel’s (in my opinion) vastly superior quality of life (cf. standard of living), the positive half of my (now somewhat rote) explanation is that I am a Jew and a Zionist, and believe in the State of Israel (though, of course, that is not enough . . . one has to like it here too).

Somewhat surprisingly, the “Jew and a Zionist” account elicits fewer looks of incredulity from the English than from chiloni (secular) Sabras (born and bred Israelis), many – or perhaps, once again, most – of whom consider Zionism of only marginally more relevance to their lives than Judaism. It is as if these people view their nationality in a total religious and historical vacuum. Whilst I am far from religious, my Jewishness has always come first, being a sine qua non of both my Zionism and my Israeliness (soon after making Aliyah, I had furious arguments on the subject with my then work room-mate . . . though I put them down to Michal being a particularly aggressive Israeli bitch). So, in relation to John’s question (above), if I had emigrated instead to Australia – i.e., if there were no Jewish factor – my reply would be quite the opposite.

The other half of my explanation to Israelis is that I never really felt that I truly belonged in England. Most people find that odd. And I can understand why. I was born in England. I went to school there. I was a BBC journalist. I then qualified as an English solicitor (no, those are not “the ones with the wigs”). I am a keen football fan (some have said even a typical English hooligan). And I like cricket even more, travelling with England’s Barmy Army to the West Indies earlier this year.

But it was that trip to the Caribbean and time spent with said Barmy Army (right) – the only semblance to an “army” being that, after a few days, you can’t wait to get out – which reminded me (not that I had ever truly forgotten) why I am not (really) an Englishman: I simply do not enjoy consuming copious amounts of alcohol for hours on end while standing at some nondescript bar stinking of urine (the bar that is . . . not me), making less sense by the pint (me this time). (In fact, thoughts and feelings fresh, I wrote the first draft of this post during the first leg – from Barbados to New York – of my return journey to Tel Aviv, on the 3rd of March.)

But it was that trip to the Caribbean and time spent with said Barmy Army (right) – the only semblance to an “army” being that, after a few days, you can’t wait to get out – which reminded me (not that I had ever truly forgotten) why I am not (really) an Englishman: I simply do not enjoy consuming copious amounts of alcohol for hours on end while standing at some nondescript bar stinking of urine (the bar that is . . . not me), making less sense by the pint (me this time). (In fact, thoughts and feelings fresh, I wrote the first draft of this post during the first leg – from Barbados to New York – of my return journey to Tel Aviv, on the 3rd of March.)

Of perhaps more significance, three of my four grandparents were born in Eastern Europe, while the parents of the fourth only arrived in England a year or so before she was born. And my father was born in Ireland. So, in what way can I meaningfully be said to be English (which many would argue constitutes a distinct ethnic group)?

I grew up in an area of North-West London that could justifiably be classified as a “ghetto”. With the exception of an Indian family and a Greek one, everyone in our crescent of approximately fifty houses was Jewish. I went to a Jewish kindergarten, primary and secondary schools, and – other than merely dutiful or perfunctory exchanges with non-Jewish teachers, my father’s hospital colleagues, our cleaner Mrs. Hart, and my babysitter Mrs. Smith – did not experience any form of meaningful interaction with Gentiles until I attended university, aged 19.

And, after discovering Amy Henderson – tall, willowy, blonde, dreamy bluey-green eyes, and bra-less under fine lambswool jumpers in the biting cold Manchester winters (if you get my drift) – on the first day of my philosophy degree, it took until my graduation, some three years later, to regain my composure (and if any of those stories about going blind are more than bobe-mayses [old wives’ tales], then, God, I am truly sorry).

But my Jewishness and ghetto upbringing aside, even the ‘true’ English – though they believe, and will argue, that they do – have little sense of identity. Ask an Englishman why he is proud to be English and he will puff out his chest and boldly tell you about the Second World War – unless you enjoy pain, reminding him that it was actually the British who fought the War is ill-advised – and, err . . . football. He might also mutter something about the flag of St. George (see the photograph above). But you won’t understand what. And neither will he.

This lack of meaningful identity can be readily observed whenever you mention an Englishman’s compatriots to him. Geordies (from Newcastle) are knobs, Mackems (Sunderland) are dicks, Tykes (Yorkshiremen) are foul, Mancs (Manchester) are horrible, Scousers (Liverpool) are scum, Brummies (Birmingham) are prats, Cockneys (London) are twats, etc. They all bloody hate each other.

So, if a ‘true’ Englishman struggles with his identity, what hope is there for the English (ostensibly) grandson of Lithuanian and Galician Jews?

Of course, in terms of nationality, I am part British (part Israeli). Being so, however, is not synonymous with being English (whatever Israeli sports commentators might believe). And, certainly as far as the Englishman is concerned, if he has to share his Britishness with the Scots and – worse still (from his perspective) – with the Welsh, he has no problem admitting a mere 280,000 Jews too.

Notwithstanding all of the above (spot the contract lawyer), I identify myself as – probably because I instinctively feel – Jewish first (and very foremost), English second, then Israeli, and British last.

British last because it is only really meaningful in terms of wars and passports (i.e., formal nationality). The Olympic Games’ Team GB does not inspire a fraction of the passion of, for example, the English football or cricket teams. Indeed, the common traits of the English, Scots and Welsh hardly distinguish them from Uzbeks or Western Samoans.

From time to time, I visit the British military cemeteries in Jerusalem (left) and Beersheba, where thousands upon thousands of World War One dead rest. It is a deeply moving experience, knowing that these young men – from towns and villages I have only heard of through my former (sad) interest in local league cricket – fell in a far-off land, fighting a war which probably meant even less to them than the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan do to today’s British servicemen. And I always wonder whether anyone still mentions – never mind visits – them . . .

From time to time, I visit the British military cemeteries in Jerusalem (left) and Beersheba, where thousands upon thousands of World War One dead rest. It is a deeply moving experience, knowing that these young men – from towns and villages I have only heard of through my former (sad) interest in local league cricket – fell in a far-off land, fighting a war which probably meant even less to them than the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan do to today’s British servicemen. And I always wonder whether anyone still mentions – never mind visits – them . . .

After everything I have written, however, how can I identify myself as English before Israeli?

Whilst you are entitled to be confused, unlike my Israeliness – which, as I explain above, is inextricably linked to my Jewishness – my Jewishness and Englishness stand alone. I am also far more English in character (cf. sense of belonging) than Israeli, which I will never truly be (other than, again, by nationality). And, in my adopted home, I am widely regarded as English – whenever I visit the café next to my office, its owner unfailingly “outs” me with a loud “Ahhhh . . . English-man!”

There are never lumps in my throat, however, when I watch A Bridge Too Far, The Bridge on the River Kwai, The Dam Busters, or Battle of Britain . . . and they are proper movies, unlike those “B” Entebbe ones. The excrutiating experience, however, of watching Yoni (Netanyahu, Bibi’s brother) slowly expire, and the exhilarating one of the freed hostages running down the ramps of those Hercules transport aircraft, touches me in a way that nothing English or British ever could.

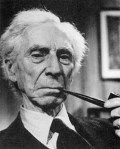

At a time when it was not common, or widely acceptable, for people to question the existence of the Deity, British philosopher Bertrand Russell (right) felt the urge to write his essay Why I Am Not a Christian (a good read, incidentally, for anyone prepared to open their eyes and mind).

At a time when it was not common, or widely acceptable, for people to question the existence of the Deity, British philosopher Bertrand Russell (right) felt the urge to write his essay Why I Am Not a Christian (a good read, incidentally, for anyone prepared to open their eyes and mind).

And today, when it is not widely acceptable to be a Jew, never mind an Israeli, I guess that I am feeling a similar need to examine and to understand my sense of identity.

And, if that sounds a bit f*cked up, well . . . that’s because it probably is.